“Really?” I replied. (This is how a 9-year-old first says, “Kiss my ass.”) there are two kinds of kids in the world... Those who can hardly get through the day without putting on a glove and chasing after a leather-covered cannonball; and those who are more literary-minded, like myself, who think baseball blows like a hot summer’s breeze.

I sucked so badly at Little League that my position in the outfield was a long distance call. I was often left out there during the change of innings, and if it hadn’t been for my mother looking for me, I would have been left out there for the change of seasons too. I hated Little League almost as much as my team members hated me. While the other players had cool ball-playing names, like “Sammy Spikes, Joe Pyro,” and “The Batman,” I was “Butter Ass.” I just did not find the hidden thrill in standing for three hours, five acres into oblivion — in the wilting sun — waiting for some asshole to find the range and drop a ball into my glove, which had all the flexibility of a dorsal fin on a killer whale.

My idea of a good time on a Saturday afternoon was to read a book and to be left alone. I was about 10-years-old, when I came across a copy of King Solomon’s Mines at a relative’s house, and finished it four days later. What was baseball compared to a story like King Solomon’s Mines? I changed schools about that time and met one of the most dynamic personalities I’d meet over the course of the next 50 years: Scott Volk. Scott hated baseball, anything that required adult supervision, and people in general who told him what to do. He got away with this attitude as he was the smartest kid in the whole school... Maybe in the history of that school. Scott and I had two things in common: geared bicycles and a hatred of baseball. One day, we unfolded an Esso gas station map, found an interesting place 30 miles away (in neighboring New York State), made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches —and left. Naturally, we did this without telling anyone, which would have been tantamount to asking for permission.

This started a weekend tradition that would last until I was 17.

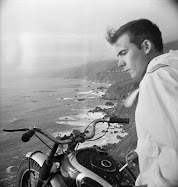

The roads we pedaled were public highways. (One of them was the George Washingtion Bridge, I-95 into Manhattan.) There were great hills that went on forever. We had no compunction about getting out into traffic, and holding our own at 45 or 50 miles per hour. Twice, local cops grabbed us and threw us off the thoroughfares. My perspective on life changed as I got older. Scott hung onto his bicycle. The last bike of my adolescence only had to be back-pedaled once, or until the 70 horsepower Kawasaki engine fired. While Scott and I remained unshakeable friends, we developed distinctly different tastes in life. Scott would think nothing of disappearing into the woods to go camping by himself, sometime for a week at a time. I loved camping too... But I liked tying my gear onto the back of the 1975 Kawasaki H2, riding off to an out of the way campground, and rolling around in Cupid’s euphoria with my girlfriend. Riding, drinking around a campfire, and getting laid was my mantra. Quite frankly, the formula is hard to beat 37 years later.

Yet, there was something of a challenge in what Scott was doing that started to get to me. On one trip, he pedaled off to one of the more remote reaches of a state park (no camping allowed), hid his bike, and set up a minimalist campsite on the Palisades. I found him pedaling back home on the shoulder of Route 9W the next day. (I sort of knew where to look and had his schedule.) Over lunch, I asked him the question that only a guy could ask another guy, who was a close friend.

“Don’t you get spooked out in the woods alone at night?”

“I did in the beginning,” Scott replied. “Last night was one of those times. I heard something about 2am that got me out of a sound sleep. It was this strange, rhythmic, lapping sound. And then I realized it was little waves on the Hudson River, 400 feet below, washing up on the bank.”

The cat was out of the bag... I didn’t like the idea of being out in the woods alone at night. This was nothing more than an advanced form of being afraid of the dark. And I didn’t like having to acknowledge that weakness either. It gradually ate away at me that entire summer, until there was nothing to do for it but get out into the woods and face my fears. The woods are a great place to go to periodically cleanse your mind. And in the mid-seventies, New Jersey still held a few truly wild places (that were not topless places on RT. 17 or bars at the shore.) My destination for a night of solitary, moto camping would be High Point State Park, just off Rt. 23. It was the first week of autumn and the camping season was about over for this place. The nights were cool... The trees were turning colors... And I would have the place to myself.

Above: The Great Notch Inn, built in 1939, still welcomes riders at the confluence of Route 3 and US-46 in New Jersey. The backdrop for this saloon is a notch in "mountain top" directly behind it. Photo from the internet.

Above: The Great Notch Inn, built in 1939, still welcomes riders at the confluence of Route 3 and US-46 in New Jersey. The backdrop for this saloon is a notch in "mountain top" directly behind it. Photo from the internet. My ride started out on Route 3, down in Hudson County. If this highway could possibly become a machine, it would be a chipper. The road design was obsolete 40 years ago, the traffic has always been utterly horrendous, and the pace can only be described as frenetic. But I was a kid then, and I didn’t give a shit or a second thought to any of this. Route 3 blended in with US-46, at Great Notch, NJ. (A bar, like an old log cabin still marks the confluence of these roads.) The stretch spawned by this unholy union only lasts for a few miles, but it is ghastly enough, with ugly strip malls, dramatically short entrances and exits from the highway, and a few diners. My immediate objective was Route 23. Route 23 peels away from the nuclear junction of I-80, and US-46 in Wayne, New Jersey, at the edge of the Willowbrook Mall, one of the first real malls in the “Garden State” and in the US. (This was one of the first places where millions of people learned about a food court.)

The traffic at this spot would have Saint Francis kicking cats in 30 seconds.

Yet 37 years ago, Route 23 was the gateway to northern New Jersey’s last working farms and dairy industry. City assholes, like myself, could see cows grazing in fields, find deer on the islands (median) of the roadway, and still run across tractors pulling steel carts (filled with manure and campaign speeches) on the road.

I loved Rt. 23... In terms of social polarity, it was as far away from Hudson county as a person could get in 90 minutes. The road was the most direct route to the northern part of the state, and its highest point. That primitive Kawasaki “ying-yinged” its way through traffic, and I found myself in Packanack Lake, one of New Jersey’s first resort and vacation spots. (It is now a bedroom community for the Metropolitan area.) This historic spot was marked by a traffic circle, a unique New Jersey attraction that replaced wolves and saber-tooth tigers as predators in the Dawinian life cycle. The road passed through Butler and Pequannock, NJ which had its own traffic circle (to try and pick off the survivors from the one at Packanack Lake).

Above: The Clove River, more of a stream actually, where I took my last trout in the State of New Jersey, more than 30 years ago. New Jersey has some of the most beautiful spots in the United States... And they really need to be preserved. Photo from the Internet.

Above: The Clove River, more of a stream actually, where I took my last trout in the State of New Jersey, more than 30 years ago. New Jersey has some of the most beautiful spots in the United States... And they really need to be preserved. Photo from the Internet.Route 23 became an expressway to nowhere for a bit up by Stockholm, NJ, where it snaked around the two reservoirs for the Newark watershed. Even then it had a curve so blind that it would have qualified Ray Charles as a sharpshooter. Mostly, the road was two lanes in each direction, but there were many places where it was half that. There was a fantastic restaurant off on the right, called Jorgensen’s Inn, where I used to take women when they needed to be impressed. The sun was getting low in the sky on this run, and I knew I would arrive at the camping area in the dark.

The road continued to climb as I passed through Hamburg, NJ. This was the town (crossroads) where my old friend Dick Matz (now in his 80’s) had a cousin Violet, who owned the local bar. Ray Bucko (now the head of anthropology at Crieghton University), Bill Matz (deceased), and I drank here once, washing down servings of pickled pig’s feet with rye whiskey and ginger ale. (We were 18.) Hamburg, New Jersey is home to the “Gingerbread Castle,” a flour mill in the 1800’s that was converted, by an an architect and a Broadway show set designer into a “storybook” attraction for children. I first came here in the early 1960’s. Hansel and Gretel took us on a tour. Rapunzel let down her hair. Jack and Jill fetched water. Witches cackled from a pit. And it was here that I learned the characteristics of an evil step-mother, which would become personified in my first mother in law. (The place is closed now, and in some disrepair. Fairy tales have passed out of fashion and two-year-olds today have cell phones and nursery school acceptance coaches.)

Above: The "Gingerbread Castle" in Hamburg, NJ. It was here I first learned about blonds, when Rapunzel let down her hair (1961). This place started out as a flour mill in the 1890's. Note mill stones in the front wall. Photo from the Internet.

Above: The "Gingerbread Castle" in Hamburg, NJ. It was here I first learned about blonds, when Rapunzel let down her hair (1961). This place started out as a flour mill in the 1890's. Note mill stones in the front wall. Photo from the Internet. Route 23 passes the picturesque Clove Cemetery, and the Clove River, a winding and wild ribbon of water from which I extracted the last trout I ever caught in New Jersey, on a day when the water froze in the eyelets of my rod. It wasn’t anywhere near that cold on the day I made this ride, but the temperature of the air dropped like a stone as the early autumn sun turned from yellow to red. Route 23 passes through Franklin, the only place on earth a luminescent mineral called “Franklinite” is found, and goes through a couple of right angle turns in Sussex. The last few miles of Route 23, just before High Point State Park twist upward on a nice run, ironically through a tiny community called “Beemerville.”

Above: The monument at High Point State Park, off Rt. 23, in New Jersey, marks the point of greatest elevtion in the Kittatany Mountains — 1,803 feet above sea level. Photo from the High Point State Park Website.

Above: The monument at High Point State Park, off Rt. 23, in New Jersey, marks the point of greatest elevtion in the Kittatany Mountains — 1,803 feet above sea level. Photo from the High Point State Park Website. A left turn along a few miles of heavily wooded ridge led to the camping area, and my headlight lit up both sides of the road. I had a bit of anxiety as I realized I would soon be setting up camp for one, in the gathering gloom of dusk, in the savage wilderness of untamed New Jersey. (The thought was utterly preposterous, even then). Now I have no trouble walking out of the woods in the dark, if I have been there all day. But going into them just as it is getting dark is just plain stupid. Why? Because that’s when vampires are feeling the most active, and are most likely to insert themselves into your circumstances.

There was one car in the campground, and I rode to the site that was the farthest from it.

I parked the bike and methodically set up camp. The tent was a “canvas” two-man number that I bought off a vendor on Canal Street in New York City for $20. I used it for 10 years and never got wet nor aggravated. There was a picnic table and a fire ring at the site. Dinner was a can of Dinty Moore Beef Stew, heated over a Svea stove. A tiny Primus light cast 50 watts over the table, with a hiss that sounded like a leak in a high pressure air hose. I dissolved a couple of packets of “Swiss Miss” hot chocolate in a cup of boiling water, and added about three ounces of rum. (This exhausted my supply of booze which was verboten in New Jersey state parks. I wasn’t carrying more as those were the good old days, when motorcycle riders were regarded as trash, and saddle-bag inspections by the authorities were not uncommon.) I moved the Primus light to ground outside the tent, and climbed in. Clothes in a ball on the tent floor, I slid into my sleeping bag, opened my copy of “Northwest Passage,” and proceeded to read, while sipping Cocoa laced with Meyer’s Dark Rum. (I had my standards even then.)

I was asleep 30 minutes later, with the screen secured on the tent, but with the door unzipped, and the lantern hissing away.

The sound of a barking dog brought me to consciousness. Night has a heady smell in the woods. The cool air slides under the darkness, intensifying the scent of the cedars, the pines, and forest duff. It also has a way of sneaking in improperly zippered sleeping bags, and finding your feet or the one muscle inclined to knot in the cold. In this case, the cold found my kidneys, reminding me that I had to piss like a yak.

But first, there was the matter of the barking dog. It wasn’t the bark of a real dog, like a Great Dane, a German Shepherd, or even a Labrador Retriever... But the yapping of a little, two-stroke dog, like a Yorkie or a Pug. And something or someone was revving the little mutt close to redline too.

“Excuse me,” said the voice of a woman. “Is anyone there, over by that light.”

My first thought was to growl, like a bear. But then I thought, “That’s how smart-assed guys like me get shot in New Jersey campsites.

“I’m here,” I yelled.

‘I’m coming over,” she said.

“I’d give it a few seconds,” I replied.

Standing naked in the mid-October night simply emphasized the need to take a leak. And anyplace was as good as likely, provided I wasn’t pissing down into my boots. The process was fairly automatic, when I realized I was casting a profile shadow in the glare of the little lantern. My concerns about making a good first impression in the harsh reality of the Primus light were unfounded as the two high-beam headlights of an approaching car bathed me in illumination. I was a senior in college... I was a varsity fencer (saber — letter and trophy)... And I was thin, taking a naked piss next to the fastest production motorcycle of the day. What the hell did I have to be sorry for?

I then pulled on my jeans and a shirt. Not once did the woman dim the lights of the car.

“I’m terribly sorry to disturb you,” she said. “But I was camping over there and wild animals were attacking each other in the brush, and I was afraid they’d come after me in the tent. Could you come over and take a look?”

The dog was one of those little breeds, whose nose is so crinkled they’re better off breathing through their asses. He snuffled in my direction once or twice, then barked in a tone of muffled disapproval. He had a name like “Ghengis Khan.”

“I’ll meet you over there,” I said.

She said thanks, and rather gave me the impression that I was expected to jump in the car and ride over with her. I didn’t doubt she heard something, but it probably wasn’t the bugling of an elk nor a wolverine challenging a bear for a big horn sheep carcass.

I stepped into my boots (without socks), grabbed the chain on the Primus light (for hanging it) and walked the 600 yards to the woman’s campsite. She had one of those Coleman pop-up tents that you could always find set up in the outdoor department of Sears in 1973. A metal cooler was on the picnic table, and her tent door was hanging askew. I walked around the tent with the Primus light swinging like a pendulum on its chain. The end of each little arc sent broad shadows dancing, but there was no evidence of a buffalo stampede or anything.

“Do you want me to let the dog out?” she asked, from the relative safety of the vehicle. The truth was that if she had let the dog out — and if a Kimodo Dragon came out of the woods and swallowed it like an aspirin — I’d have laughed myself into insanity.

“No,” I said, shaking my head, looking down at the ground like I expected it to yield a paper printout of the evening’s activity.

Then I sauntered over to her picnic table, put down the Primus lantern, and lit a cheroot, which was a crooked as a congressional mandate.

She got out of the car, carrying the stupid dog, and sat at the table, looking at my cigar like I had dog shit dangling from my lip.

“So what did you hear and where did the noise come from?” I asked, trying to sound like a professional hunter on the trail of a wounded gazelle. I looked directly into her eyes, and gave her a very mild exposure to what would become known as the patented Jack Riepe Battered Baby Seal Look and Pre-Foreplay visual invitation.

She told me she heard a vicious tussling in the trees, and then a kind of scream, followed by the sound of something being rendered into pieces. Her expression, highlighted by the lantern, took on the characteristics of somebody telling a horror story to a six-year-old.

“Aaaah,” I replied. “Well, that’s easily explained. Rabbits constitute the basis of the animal kingdom diet up here, in wild New Jersey, and foxes, coyotes, weasels, and owls jump them all the time. When caught, the rabbit screams like a human baby.”

“My God,” she said, “They do?”

I nodded and said, “What you probably heard was a rabbit meeting its maker, and then being processed for dinner. You were never in any danger.”

“How come the dog didn’t scare the animals away?” she asked, looking at me with a bit more respect.

“Because your dog isn’t much bigger than a rabbit and a fox, a coyote, or an owl would have no qualms about doing the same thing to your dog.”

“Will the owl or the fox, or the weasel come back?”

“As long as rabbit is on the menu,” I smiled. “I think you should be okay, now. Good night.”

I got up to walk back to my tent. I found myself wondering, “How far is she going to let me go before she says...”

“Jack...,” Said Carole. (Not her name.) “Would you like to stay here tonight? I have sandwiches and stuff.”

Carole had a pretty face, a nice shape, and an intriguing ass. But she had the chirpy manner of a woman who taught second-graders how to share. (I was the scourge of the second grade. I once made the sweetest — kindest — old Catholic nun call me “a son of bitch” in less than 15 minutes.) Carole was about 27-years-old, which made her 6 years older than me. As far as I was concerned, she was ready to collect social security. I thought of my own girlfriend, about 70 miles to the south. Roxann was two-years older than me, an Italian beauty with skin the color of honey at sunset, waist-length black hair, and the kind of voice that could take the sting out of sunburn. I wanted my own girl tonight... My own red-hot sex kitten of a girl was home, watching my Labrador Retriever, a dog that never made a noise like a hand-held vacuum cleaner choking on a lint ball, because I had to prove something.

Carole suggested that we could play cards in her tent, try to identify constellations from a book she had, or even just talk. I started to waver.

“Do you have anything to drink? Coffee.. Irish Whiskey?” I asked.

“Herbal tea,” she responded, holding up a Thermos.

That did it. I was ready to hang a pork chop around her neck, tie her to a tree, and whistle for Kong.

“Great.” I flashed a genuine smile that would have delighted an aluminum siding salesman. “Why don’t we do this? Pull your car around to my tent. You and the dog can sleep on the back seat of the car, with the doors locked. At dawn, we’ll go for breakfast, at the place in Colesville.”

A minute or two later, I was back in my tent, which was again the focus of her headlights.

“You can turn them off now,” I said. I had to say it three times.

It was full daylight and nearly 7am, when I rose for the day. Carole’s car was gone and I took another forceful piss with male biker impunity. (Guys love taking a piss outside, and getting the stream up as high as a Kodiak bear can leave scratch marks on a tree.) I broke camp in record time and the Kawaski started on the first kick. I snicked it into first gear, and the shifter fell listlessly to the ground.

“What the fuck,” I uttered in a precise mechanical assessment. A “C” fastener had vibrated off one of the pivot points and the shifter had come apart. I replaced the fastener with a bit of twisted wire. A gas station down in Sussex would sell me another fastener for a quarter.

The bike restarted and I was OTFD (Out The Fucking Door)a second or two later. I had breakfast at this little joint in Colesville... And I pushed that H-2 as fast as I dared on the way home to take Roe out to lunch.

But that is not the end of the story... Not by a long shot.

Four years later, Ricky Matz and I were clawing our way up Route 23 to his place in Pennsylvania. Route 23 exits New Jersey at the spot where it meets Pennsylvania and New York. Ricky was riding a Norton, and I was still on Tojo’s Revenge. We stopped for a couple of beers in a joint where I’d gotten lucky once before, but the lightning didn’t strike twice this time. Our ride can only be described as “spirited.” Once again, dusk found me rocketing up toward High Point State Park, this time with Matz about 70 feet behind me. Our goal was to go over the mountains at High Point, and hit Pennsylvania about the time the action was heating up at a bar called “The Acorn.”

The suspensions on these motorcycles were so primitive that our headlights vibrated with a strobe effect that added to the excitement. And in the strobing effect of my headlight, there appeared the dull shine of a guardrail, where the road curved to the left.

The gentle Twisted Roads Reader will now chose the paragraph that they liked best. Should you decide to leave a comment, please indicate your selection...

First Choice (A):

Out of options, I laid the motorcycle down, relinquishing all control, so I could come to halt, gradually, through road friction and by slamming into the guardrail, knowing I would minimize my own injuries.

Second Choice (B):

The finely tuned suspension of the 1975 Kawasaki H2 Triple instantly lived up to its reputation as “The Widow Maker,” went into a tank slapper, and hurled me to the pavement just as the bike careened into the guardrail.

Third Choice (C):

I slammed on the primitive brakes, went into a skid, and fell off the bike on the low side as it whacked into the guardrail.

The bike went down at 45 miles per hour.

The handlebars were bent... The tank was dented... The headlight was out of focus... The clutch lever was oddly bent, but not broken... The left mirror was shattered... But the forks seemed okay... The Kawasaki restarted. Ricky rode the wreck to the ranger station at the top of the hill.

A passing farmer gave me a lift in his truck, and Ricky walked back to retrieve his Norton. I had a torn sleeve on my fatigue jacket and no injuries. My shitty candy-apple metallic helmet was scrapped to shit.

The park ranger/cop was the world’s nicest guy. He plopped me in a wooden rocker, got me a Coke, and was very helpful in letting us park the wreck behind the station for the weekend. He asked me if I wanted an ambulance. (What I wanted was to hit the Acorn and get laid for the weekend.) He could see that neither Ricky nor I was intoxicated, and mentioned that the guardrail I hit was very good for local tow truck business on the weekend. He did not ask how fast I was going, which was also good, as I was speeding and would have lied to him. (I have an honor thing with going fast on a motorcycle and lying to the cops about it later.)

The officer was more like a combined ranger and cop, as he had a gun and handcuffs on his belt. Neither Ricky nor I exactly conformed to the definition of scooter trash. He treated us like men, which we barely were, and we tried to meet his expectations for politeness. (And once again, there was no liquor nor controlled substances on our bikes.)

Ricky explained that he had a car across the state line in Damascus. Pennsylvania — about 50 miles away. He’d go and get it, then come back for me. It was 8:30pm, and the station was only open until 10pm. The ranger said I was welcome to wait with him, and then sit out on the porch, until Ricky returned, about midnight. Ricky looked at me, and smiled. The dim tailight of the Norton faded over the crest of RT. 23. I could hear the engine growling in the dark night air.

The ranger was a sociable type and we got to talking. I mentioned the night (three years before) that I spent in the campsite with the woman and her little dog, right in the middle of his jurisdiction. And now, I will add one more detail to that story. The woman had a name that was hard to forget. It was a household word. I remembered it perfectly then, as I remember it now. The cop remembered it too... And found it in a file.

At dawn that day, Carole Tapper (not her real name) drove out to the ranger station with her useless little dog. She waited until the office opened, around 8am, and filed a report. An officer escorted her to the campsite (and if it was this same cop, he probably helped her fold the tent). Park rangers examined the camp site, and found — are you ready for this — mountain lion tracks in the duff behind her tent.

The park cop/ranger then told me that this was one of New Jersey’s best kept secrets... That big cats occasionally turned up in solitude. And that if you knew where to walk, you could still traverse the northern end of the state without coming up on a house. (I was secretly delighted that I had the good sense to mind my own business, lest my name appear in the same report.)

The hour was a few minutes from 10pm, and the officer started to lock the place up. He invited me out to the porch, just as Ricky pulled up, in a 1971 Dodge Dart, the official car of Catholic Convents throughout the US. Ricky’s Dart was called the “Yellow Jacket.” It was painted electric piss yellow, with black doors (two-door) and a black hood, from which protruded a two-foot tall chrome scoop, that sometimes belched fire. The car was powered by an eight-cylinder Chrysler atomic reactor.

Powerful stereo speakers pounded the atmosphere, as Jethro Tull’s epic work of enduring romance — “Locomotive Breath” — announced that Friday night was still on. We’d make “The Acorn” in plenty of time.

©Copyright Jack Riepe 2011 All rights reserved.